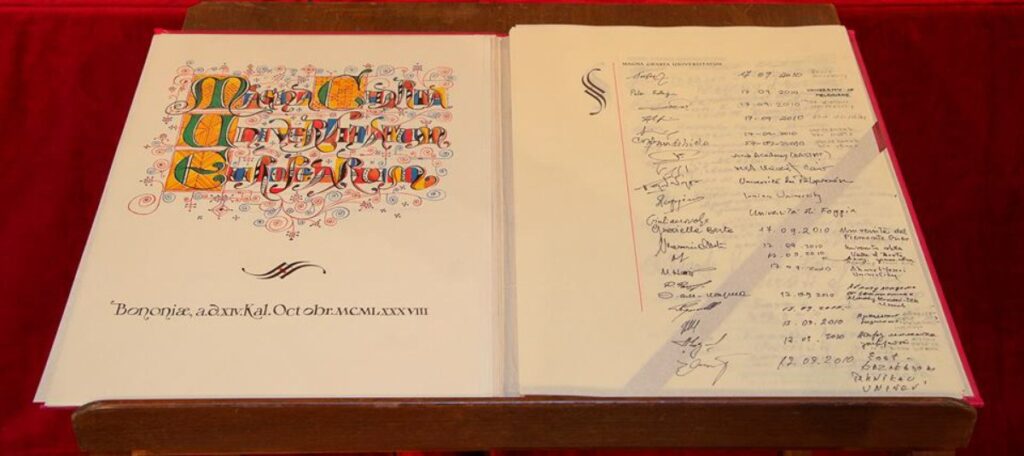

A university culture centered on the student, not on the faculty or administration. The authority of governing is gained through the existence of levels of participation and cooperation in decision-making. The picture above shows the signature ceremony of the Magna Charta Universitatum signed in Piazza Maggiore at Bologna on September 18, 1988, by 388 Rectors of worldwide main universities. They were representing the Autoritas Universitatum of the traditional and new higher education institutions when the University of Bologna was commemorating one thousand years of its existence.

The competent authority is slowly replacing charismatic, dictatorial or democratic authority. That is, professional, technical, administrative and academic preparation is more relevant when it comes to managing institutions than the power of empathy or innate leadership qualities, although these are of course important. The evolution of the world of knowledge requires university leaders who combine general education with specialized training in the management of services. The university sphere, which is dominated by a ‘knowledge elite’, by a multitude of prima donnas and by an excessive loyalty to academia, has rejected participating in the process of administration. In fact, the administration is looked down on by many university groups. However, my position is far away from the corporate style. See my view on this issue (2021) at: «Corporate management is an unfit model for education».

The role of the university rector or president is associated with political, economic or social power, not as in previous centuries, in which this figure was associated with academic, cultural, or spiritual power. Moreover, most top-down power systems at universities or those in which a president is the highest authority, whether democratic or otherwise, place almost total responsibility in the hands of the rector. Because of the power exercised by the rector, it is often impossible to know whether he or she depends on the management board or vice versa.

This is the result of legislation that reinforces centralized and even sometimes autocratic power. In contrast to this, the tasks that a rector is required to carry out are, in academic and administrative terms, clearly absurd. Thus it often jokes that the essential qualities of a president or provost are that he or she should possess the wisdom of King Solomon, the strength of Hercules, the shrewdness of Machiavelli, the patience of Job, and the psychological insight of Freud. That is a lot to ask. And perhaps today we might even add the entrepreneurial vision and financial know-how of Steve Jobs.

The governability models employed and the manner in which decisions are taken at a university tend to be closely linked to whether the university exists within a society that is democratic or authoritarian. The leader of a university is conditioned by this fact, especially in his or her relationships with political authorities or pressure groups and the manner in which he or she exercises his or her functions in relation to the university community. It should also be noted that not all management processes in the entrepreneurial system can be transferred directly to universities. Concepts such as productivity, order, and effectiveness lend themselves to very different interpretations when one is talking about an educational process as opposed to manufacturing cement blocks.

The governability models employed and the manner in which decisions are taken at a university tend to be closely linked to whether the university exists within a society that is democratic or authoritarian. The leader of a university is conditioned by this fact, especially in his or her relationships with political authorities or pressure groups and the manner in which he or she exercises his or her functions in relation to the university community. It should also be noted that not all management processes in the entrepreneurial system can be transferred directly to universities. Concepts such as productivity, order, and effectiveness lend themselves to very different interpretations when one is talking about an educational process as opposed to manufacturing cement blocks.

Nothing is more frustrating for the body of students and professors than for an authority to be unacquainted with university problems, particularly when that authority tries to solve these problems by implementing measures that are strictly administrative or political. Academic problems, scientific debate, and attitudes that are critical of the system or of society are typical of the university community. They will always exist, but they are diffused and mediated by an understanding and conciliatory authority who is able to accept the differing loyalties of the heterogeneous academic community. This authority should never attempt to quash debate over ideas and problems because it is precisely this debate that is one of the mainstays of university life.

Therefore, even in more extreme cases a non-belligerent approach to the university, as a platform for social criticism, in light of the times and the social, cultural, and economic situation of the national or international community, cannot be curtailed by imposing rigid or authoritarian lines. It is precisely this criticism and controversy that push society to seek a reformist consensus that improves the quality of life.

university, as a platform for social criticism, in light of the times and the social, cultural, and economic situation of the national or international community, cannot be curtailed by imposing rigid or authoritarian lines. It is precisely this criticism and controversy that push society to seek a reformist consensus that improves the quality of life.

However, there is a trend at universities large and small to develop authoritarian systems of centralized, top-down government or to form systems of academic resistance. Decision-making is made evident by a hierarchical system that is based strictly on the delegation of power and hardly ever on epistemological authority. Certainly, it is easier to take decisions under an imposed or self-imposed authoritarian system, especially in an environment such as a university, in which every member thinks of himself or herself as an autoritas. For this same reason, decisions are taken but never fully implemented. Thus, I have always maintained that any educational reform is doomed to failure if the people who are affected by it are not the protagonists of this reform and are not convinced of its worth (Escotet, 2009, 2021).

The exercise of authority at a university requires a dialectical discussion that flows on a three-dimensional plane, as life does, from top to bottom, from bottom to top, and from one side to another, making it a spherical relationship and not a circular one. It is a system of multiple entries and exit points, which must be viewed in a holistic and not a fragmented way. It can only be measured with instruments that are able to detect its volume and not just its length. That is, whilst most companies outside the realm of education move in a linear, Newtonian manner involving relative prediction, an educational enterprise moves in a world of uncertainty and, therefore, one of the complex processes. For this reason, authoritarian systems at universities are usually just short-term solutions, which makes one wonder what may happen in the future.

Consequently, it is indispensable for university leaders or managers, whether presidents or rectors, provosts, deans, directors, department chairs, or collegiate bodies, to be convinced that the way of governing a university is by seeking consensus rather than resorting to a ruling by decree. Consensus in university administration is based on the principle that the person who presides over the institution is primus inter pares, that is, first among equals. In academic terms, the majority is not always right. It is worth mulling over Russell’s claim that the fact that an idea is shared by the majority does not make it true; and in view of how stupidly much of humanity acts, an idea conceived by the majority is more likely to be false than true.

Although – logically – it has limits, the consensus is a means for decision-making in university development that is of enormous value because it accepts the fact that both majorities and minorities may be right or that both may be wrong. Borrero (1993) claims that consensus in decision-making at universities is both legitimate and necessary. Research has in fact shown that the practice of consensus tends to have a unifying effect, whereas the triumph of the majority over the minority leads to confrontations that make the implementation of these decisions much more difficult (Escotet, Aiello & Sheepshanks, 2010).

Although – logically – it has limits, the consensus is a means for decision-making in university development that is of enormous value because it accepts the fact that both majorities and minorities may be right or that both may be wrong. Borrero (1993) claims that consensus in decision-making at universities is both legitimate and necessary. Research has in fact shown that the practice of consensus tends to have a unifying effect, whereas the triumph of the majority over the minority leads to confrontations that make the implementation of these decisions much more difficult (Escotet, Aiello & Sheepshanks, 2010).

Management professionals are generally well acquainted with techniques that seek consensus and they know when a discussion should continue and when it should end. Undoubtedly, a consensus is a system for decision-making that is much more complex than other forms of participation. However, the governability of a university is built up by negotiating with people and convincing them —that is — by accepting the nature of what is an institution of people and not of objects and by nurturing the spectrum of the human condition. It is in itself simply one more aspect of the education of students and professors (who are permanent apprentices), just as authoritarian attitudes and habits would be if these students and professors operated in an environment in which there was no dialogue or tolerance.

In short, we need to build a new university culture that breaks away from a mission to satisfy the corporatist yearnings of the professor, the endogamic academic practices (2022), or the authoritarian appetite of the administrator, leaving the true protagonist, the individual who learns, on the fringe of the essence of the university. A university culture centered on the student, not on the faculty or administration. We must remember that the role of the rector was exercised by a student in the origins of the European universities as Bologna or Salamanca. It has been endlessly repeated that the student is the main actor in the learning process—and the opposite has been endlessly practiced. At least, student learning was the major aim at the origin of Bologna, one thousand twenty-three years ago. It is time to leave behind demagogic approaches to teaching.

REFERENCES

Borrero, A. (1993). The University as an Institution Today. Paris: UNESCO Publishing and IDRC in Ottawa.

Escotet, M.A. (2021). Corporate management is an unfit model for education. Retrieve from Scholarly Blog on December 20.

Escotet, M.A. (2021). Las políticas universitarias para una educación a lo largo de la vida. XVII Congreso Nacional y IX Iberoamericano de Pedagogía and WERA Congress 2021. Santiago de Compostela, Spain, July 7.

Escotet, M.A. Martin, A. and Sheepshanks, V. (2010). La Actividad científica en la universidad. [The Scientific Activity at the University] Buenos Aires: UNESCO-UNU Chair and U. Palermo.

Escotet, M.A.(2009). University Governance and Accountability. In GUNI (Ed). Higher Education at a Time of Transformation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 126-132.

Escotet, M.A. (2004). Contemporary Forms of University Government and Administration: Historical Vision and Perspective. Centro di studi universitari. Rome, Ateneo Antonianum, May 26-28.

Federación de Jóvenes Investigadores (2022). Endogamia y corrupción generalizada en la Universidad española: ¿Seguimos mirando hacia otro lado? El País, 18 de mayo.

Levy, Daniel C. (1993). El gobierno de los sistemas de educación superior. Pensamiento Universitario, 1(1), 3–20.

Russell, Bertrand (1957). Marriage and Morals. London: Liveright.

____________________________

©2022 Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing.