- June 24, 2023

- AI, EdTech, Education, Educational Theory, Humanism, Learning, Liberal Arts, Philosophy, science, Technology

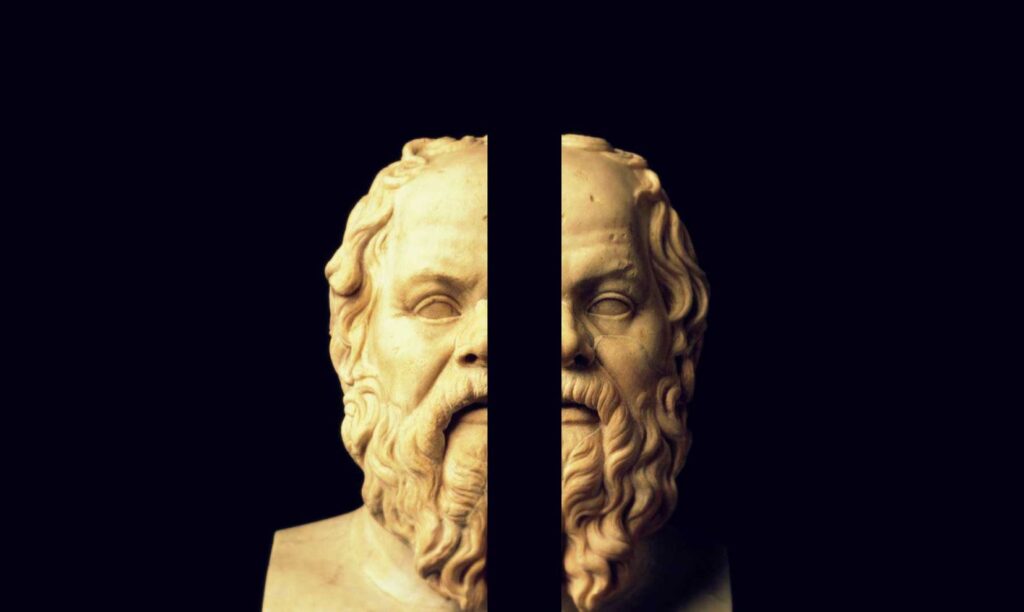

The segmentation of fields of knowledge has led to the fragmentation of language, producing a generation of professional people incapable of communicating between one branch of knowledge and another and, increasingly, between the cultures of science and the humanities. The false dichotomy between formative education in the sciences and the arts requires a radical change in teaching and learning strategies. At the same time, another dichotomy in the teaching process between humanism and educational technology is a dangerous fragmentation that is happening now more than ever.

What has become known as educational technology sprang from behaviorist psychology and philosophical positivism and gradually included systems and communication theories? The different incidences of each of the contributions in each place, and the passing of time, have shown all too clearly the shortcomings of the atomistic and mechanistic formulations adopted by educational technology and which are now totally incompatible with new learning systems, more comprehensive and tending to foster the inventiveness and personal involvement of the students.

Present-day studies of educational technology include models of cognitive, metacognitive, and epistemological learning instead of purely mechanism forms, systemic-cybernetic concepts, open and interactive as opposed to closed systems, and two-way communication processes instead of one-way educational communication. In other words, the revision of educational technology has covered every aspect, from the old fondness for behaviorist aims to the principle of effectiveness as the ultimate goal of technology.

The restriction of educational results to operative objectives, the feature of educational technology which gave rise to programmed instruction, reduced the process practically to the acquisition of behavior patterns, psychomotor skills, and very elementary knowledge, reducing education more or less to a model of instruction. Quite rightly, this has been one of the arguments against specific programs that overlook such objectives as the development of a capacity for criticism, personal inventiveness, personal integration of culture, and the acquisition of cognitive and meta-cognitive strategies, all of them essential targets in the conception of education as the integral development and growth of the individual. These fundamental goals are the beacon lights of education, but it must be remembered that they are reached only step by step. Personal responsibility, critical capacity, or inventiveness are not achieved immediately; they are approached by successive approximations, ticking off intermediate objectives along the way, some of them operative and concrete. This means that the technological program for ambitious final goals cannot overlook the interrelations leading to them.

As far as effectiveness goes, it is evident that this cannot be understood as attainments that strengthen or confirm undesirable situations in the learning relationship, nor as a process of irrelevant learning for personal or collective advancement. The principles of pragmatism and efficacy so widely heralded by educational technology up to now must defer to the higher claim of the noble aims of education, and to this end, the nations must follow the path of greater social justice and greater personal dignity.

As far as effectiveness goes, it is evident that this cannot be understood as attainments that strengthen or confirm undesirable situations in the learning relationship, nor as a process of irrelevant learning for personal or collective advancement. The principles of pragmatism and efficacy so widely heralded by educational technology up to now must defer to the higher claim of the noble aims of education, and to this end, the nations must follow the path of greater social justice and greater personal dignity.

The moment has come to say to educational researchers and those familiar with educational technology that their knowledge must not be used indiscriminately. Since the 1950s, when the first activities of educational technology appeared, we have seen how few of them have been of any use at all to collective progress. It is time to analyze who is being really helped by programs of educational technology and draw relevant conclusions as to how they can be placed in the modernization of society.

There is already talk of new technology, artificial intelligence, and, most relevant for education, Generative AI, but the name is unimportant. What does matter is the use to which it will be put in the future, which cannot be other than the improvement of education and learning, by which we mean the fullest development of each individual in a social milieu providing freedom, justice, and opportunity for everyone. The deep-rooted problems of education in developing countries, and the new ones arising from the force of history, still need technology for their solution. Still, it must be a renewed, appropriate technology able to respond adequately to these needs.

However, the rise in criticism of the negative consequences of the misuse of technology in the past, which may even extend into the future, leads some people to oppose its application in the field of education. Their argument is that this will protect the educational system from the dangers of alienation, dependence, and so on, which have beset other social sectors.

It seems obvious that the education system cannot escape the social context. To renounce the use of technology in the educational system would make sense only in a society that renounces it wholesale in all the other sectors: health, nutrition, production, communications, science and technology, etc., and this for a very obvious reason: the system of education is a means of preparing for full incorporation into social life.

Humankind could have chosen other paths of progress and might even have stayed put. The choice, however, was for industrialization, digitalization, technology, and innovation. The force of history makes this process all but irreversible, although it can and must be reorganized. As developing countries opt for their incorporation into the mainstream of nations, they must accept and adopt the technology. Otherwise, they will remain wedged in unjust social structures or in a permanent state of dependence. More than a question of whether technology is worthwhile, the problem is to decide which type of technology is suitable and how it can best be incorporated. It is a need in the world to put educational technology at the service of human beings and not the opposite. Both technology and humanism must coexist.

The critical attitude that should be adopted towards the indiscriminate use of technology must not lead to the preservation of obsolete school structures that cannot satisfy the demands of this Twenty-first century. Just as there could have been an uncritical sharing of technological proposals recently, totally unsuitable to the cultural reality of the poorest countries, now there might be an importation of criticism of this technology in education, criticism that arose in the more developed countries after a massive application of their own technology, but that could acquire a different meaning among educators in countries in transition. Some theoretical proposals have nothing to do with the requirements of community importers of technology. For wealthy societies in a digital age, in the exponential expansion of artificial intelligence, technology may even be a luxury and a necessity; for those less developed, it is just a necessity.

©2023 Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing.