- May 18, 2024

- Aging, Cognition, Cognoscitivo, Emoción, Emotion, Ensayo, Envejecimiento, Essay, Psicología, Psychology

The critical undertaking when reaching old age, if memory continues to govern our cognitive future, is to keep hope and romanticism intact, the desire to contribute and keep creating, to expand the feeling of love as far as the horizon can be perceived, to continue observing the world with the eyes of experience and the curiosity of a child for the mysteries of that space in which cosmos where one’s existence has taken place.

Quandary is also known as uncertainty, but the lack of certainty is not always a result of a lack of knowledge or security. In fact, in Ortega’s philosophy on change, it is suggested that we should have the wisdom to face and respond to processes of uncertainty, to the quandary itself. Deep down, some states of uncertainty are fundamentally psychological, intangible within people, and not external to them. The world of emotions is also a world in which these forms of human complexity are debated.

The thought by Richelle E. Goodrich reinforces the differentiating concept between sensation, perception, and reality, between the world of certainty and uncertainty, where emotional dilemmas flow. “You may be the only person left who believes in you, but it’s enough. It takes just one star to pierce a universe of darkness. Never give up.” Feeling discouraged does not mean giving up. Feeling sad does not mean that joy does not exist. Feeling alone does not mean you are alone. Feeling anxious does not mean you are in danger. Feeling the loss of somebody close to you does not mean you have nothing. Feeling angry does not mean you lose control. Feeling sorry or ashamed does not mean you are to blame. What you think and feel are different from what it is.

The life cycle involves permanent learning with different stages that must be gone through and in which we acquire maturity. People must face and balance opposing forces, requiring synthesis in each of them. In adulthood, the challenge is finding the balance between one’s integrity and discouragement or, what is the same, between wisdom and uncertainty, or what is similar between the value of experience in predicting events and the uncertainty caused by external variables and intervening and unpredictable variables. The first is integrity, understood as fidelity to those universal principles that have allowed us to create a culture, recognize ourselves as travelers of the same planet, and be faithful to our immediate environment and the other great environment that encompasses all humanity.

Those who have learned to take care of themselves and to preserve their environment and that of other beings will undoubtedly accept their triumphs and disappointments, inherent to the fact of living, with a gradual process of maturation throughout their life cycle. This is what we can understand through wisdom. As for discouragement, this would translate into despondency in the face of the uncertainty of what remains to be experienced, feelings of loneliness, desolation, and the questioning of everything that was taken for granted and immutable.

Senescence is a stage of introspection, of balance between the past, present, and future. This interiority means not only a review of the history of one’s own life but also the fact of reconsidering past behavior, admitting mistakes, and valuing our contribution to the well-being of our loved ones and the other beings who have accompanied our lives. We must recognize that on many occasions, wisdom appears with disappointments. Sigmund Freud maintained that in this emotional work of accepting what has gone and valuing what is preserved. In other words, we remember, repeat, and elaborate on the experiences that have given meaning to our intimate personal lives.

Upon turning 80, the philosopher Bertrand Russell told journalist Romney Wheler that he had lived 80 years of “changing beliefs and immobile hopes.” Those are the words of a philosopher who lived and suffered through the terrible years of that century that engendered and endured the tragedy of two world wars. From our point of view, the critical thing when reaching old age, if memory continues to govern our cognitive future, is to keep hope and romanticism intact, the desire to contribute and keep creating, to expand the feeling of love as far as the horizon can be perceived, to continue observing the world with the eyes of experience and the curiosity of a child for the mysteries of that space in which the cosmos where one’s existence has taken place.

Identity is always constructed within a social context that can be a facilitator in terms of personal enrichment experiences. Today’s society has progressively embraced a paradigm of active aging, reflected in the creation of multiple programs to promote it. Most of them are framed in lifelong learning, without interruptions, physical activity, real or virtual travel, and volunteer actions in favor of society, with appreciable benefits for those who practice them. Indeed, the physical and cognitive aspects are fundamental for the healthy aging of people, but equally important is the care of emotions, an area that still needs to have its place within these society programs.

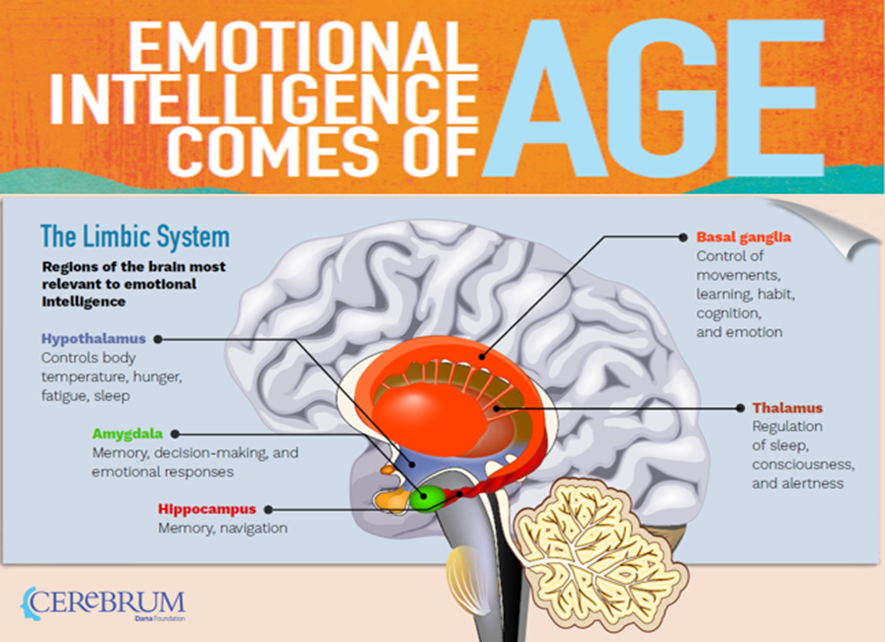

Emotional intelligence, which involves parts of the brain that remain active from birth to old age, requires constant stimulation, particularly during the aging stages. We consider it transcendental, as evidenced by longitudinal studies, that those who have considered work as a vocational part of their existence, as an ethical commitment to the generations that follow them, should not allow the years they have left to become years of mental and physical idleness. It is time to revitalize creative activity, volunteer for others, and engage in productive work as a fun, not a retiree, endeavor.

As the years of maturity go through and the end of life’s journey approaches, if this process is emotionally healthy, people’s desires for solidarity and compassion for those who suffer emerge much more intensely. They experience generosity of feelings and an immense capacity to love genuinely without seeking anything in return. Nevertheless, they can also discover, with a mixture of pain, helplessness, and skepticism, the narcissistic cult of various actors in society, the fanaticism of ideas, the capacity for destruction of human beings, the vanity of power, and the tyrannical use that is made of it.

Often, the vestiges of a society without intergenerational feeling, a genuinely ecological feeling, park the repositories of the experience when they still have memory and condemn them to lose it in the prison of oblivion to which they are subjected. This fact is contrary to what happens in the American Indian tribes and some Eastern cultures, in which they have to feel proud and wise that they cultivate the value of the experience of their elders because, in that aspect, they are light years ahead of our arrogant societies of waste, of inconsequential leisure, of the here and now, and the cult of narcissism and extreme selfishness. For this reason, George Santayana’s famous and wasteful thought that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” comes to mind.

Our emotions and ability to process them are decisive issues when achieving healthy and active aging. Let us remember that aging is knowledge. In the words of the intellectual and author of the famous Diary, Henri-Frédéric Amiel, “Knowing how to grow old constitutes the masterpiece of wisdom and one of the most important parts of the great art of living.” Learning to live is also learning to die with dignity, joy, and hope.

References

Amiel Henri-Frédéric (2023). Fragments d’un journal intime (Éd.1922). Vanves: Hachette Livre.

Goodrich, Richelle E. (2015). Smile Anyway: Quotes, Verse, and Grumblings for Every Day of the Year. Amazon: Create Space, Kindle Direct Publishing.

Russell, Bertrand and Wheeler, Romney (1952). A Life of Disagreement. The Atlantic, August Issue.

Santayana, George (2011). The Life of Reason: Introduction and Reason in Common Sense. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

_______________________

© 2024-2025 Miguel Ángel Escotet. All rights reserved for the English and the Spanish versions. It can be reproduced by citing the source and the author.