- March 9, 2024

- Accountability, Education, Ethics, Higher Education, HigherEd Assessment, HigherEd Management

Universities must be accountable, yes, but to whom? Whether public or private, universities cannot be exempt from regulation, but it should come in the form of self-assessment and a duty to society, not politics.

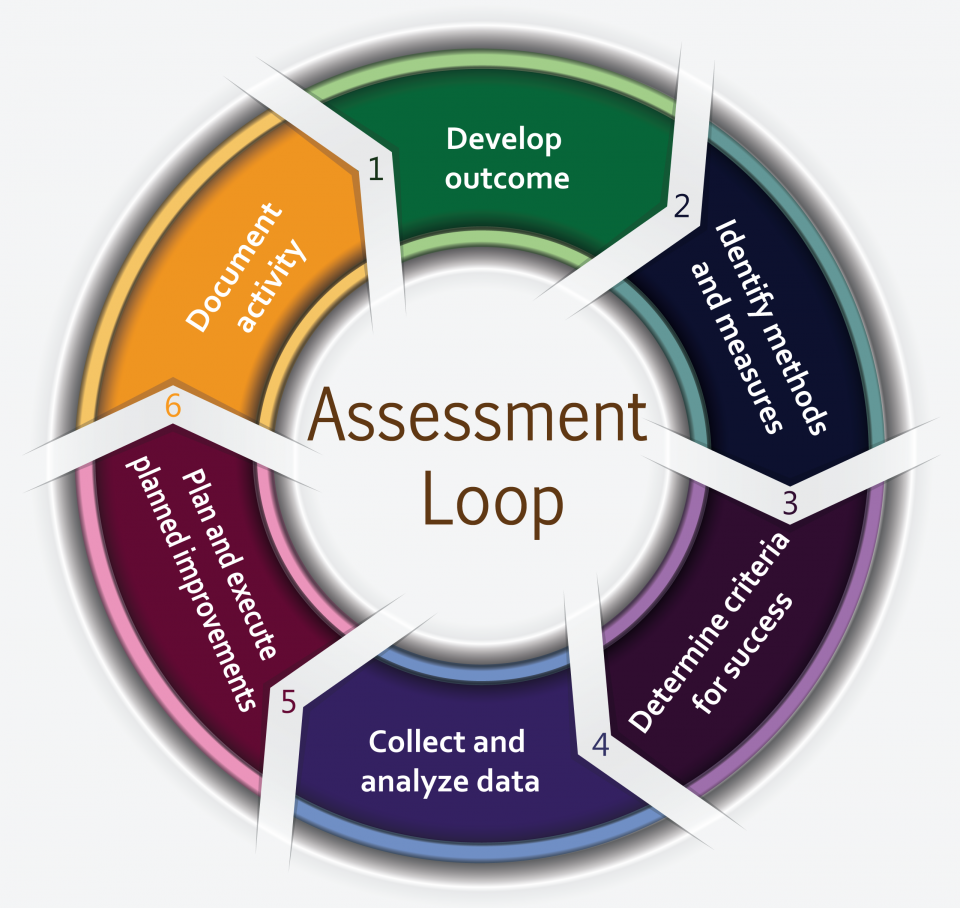

The most radical critics suggest that the best law on university action is one that refers to an institution’s mission and obliges it to fulfill it. Making the links between aims and means, between internal and external achievements, is part of that accountability process. However, control is a necessary mechanism only in as much as it teaches institutions to develop self-assessment, self-control, and regulation rather than perpetuating control in the form of ‘vertical authority’ systems. See the six stages in the following picture that can be used for self-evaluation or self-assessment.

University academic and administrative processes have certainly improved due to new management techniques and technologies. However, while managerial skill building is not yet up to scratch in many higher education institutions, business techniques have not been sufficiently adapted to the university culture and mission. Management appropriate to manufacturing companies or service providers may not be effective in the administration of knowledge generation and transfer in university environments.

It is a source of great concern to see how certain universities are being dominated by corporate administrators with no academic experience and by bureaucratic and management structures and techniques that equate an institution that generates and disseminates knowledge with a washing powder manufacturer, a multinational travel agency, or a banking loan system.

Western universities have always been subject to tension between the university community’s pursuit of independence and the pressure exerted by social forces, whether public or private, to control them. Autonomy is a prerequisite, we say, yet the concept of university autonomy has been and still is a trend that lends itself to different interpretations.

The genuine autonomy of universities has been replaced in numerous instances by a system of pursuit of power as an extension, within universities, of the work of political parties in democratic societies or the debasement of autonomy in single-party societies or those ruled by autocratic governments. In some cases, under the pretext of strengthening autonomy, these practices have hindered universities’ independence to the extent that the governing party controls universities or the opposition uses this independence as a weapon against the government. The most significant example of political or economic control has been the subordination of universities’ sources of funding to the control, not of society at all levels, but to changing political interests and economic pressure groups.

The ultimate aim of the university accountability process should be to guarantee universities maintain the principles and ethical practices that protect the public (and public funding) from fraud, the type of fraud that can result from the gap between what is said and what is done, between what is offered in academic terms and what is taught. Intervention should be justifiable to check whether each institution’s qualitative and quantitative indicators to measure quality are met.

can result from the gap between what is said and what is done, between what is offered in academic terms and what is taught. Intervention should be justifiable to check whether each institution’s qualitative and quantitative indicators to measure quality are met.

However, other types of intervention, whether direct or covert, threaten creative processes, research, and the pursuit of truth. When it occurs, this coercion of freedom has been a significant factor in many university crises. It has also resulted in a new ethos whose values, attitudes, and beliefs have moved away from academic and administrative independence. Paradoxically, this has served to reinforce the disengagement of universities from civil society on a national and international scale.

This politicization of higher education is a symptom that affects universities worldwide to a greater or lesser extent. Universities demand national and transnational state agreements that overcome these forms of polarization and interventionism. But they also cry out for control and counter-control systems that combine the freedom to create, teach, and learn with the obligation to disclose objectives’ fulfillment (or lack).

Whether public or private, universities cannot be exempt from internal and external control, and there has been a clear move towards implementing institutional assessment and accountability processes since the end of the twentieth century. However, this process of accountability should not be influenced by the government in power or by political bias within universities. This is the domain of the university community through self-assessment and through the society to which it belongs — the former should commit to being accountable to the latter.

Whether public or private, universities cannot be exempt from internal and external control, and there has been a clear move towards implementing institutional assessment and accountability processes since the end of the twentieth century. However, this process of accountability should not be influenced by the government in power or by political bias within universities. This is the domain of the university community through self-assessment and through the society to which it belongs — the former should commit to being accountable to the latter.

Let’s not forget that universities are part of the wider education system, closely related to other educational levels and providers, social institutions and business enterprises, and to the productive and industrial sphere. Universities and the rest of the education system must combine their programs to ensure that the transition from one level to another is integrated and flexible. In the same way, they must create communication channels between the different non-formal and informal education systems that exist in society.

Autonomy will always be subordinate to the necessary response of universities to the needs, demands, characteristics, and transformations of the social system of which they are a part. Today, more than ever, the trend should be for universities to make their autonomy compatible with their inevitable interdependence and be transparent and accountable to the society to which they serve.

References

Escotet, Miguel Angel (2017). Análisis Multivariado en Ciencias Humanas. Miami: TransCampus. 478 pages.

Escotet, Miguel Angel (2006). Governance, Accountability and Financing of Universities. In Guni, Higher Education in the World 2006. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave MacMillan. Pp 24-40.

Escotet, Miguel Angel (1998). Manual de Auto-Evaluación de la Universidad. Bogotá: Editorial de la Universidad de los Andes/UNESCO, 224 pages.

——————————

©2024 Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing. This updated essay was originally published by The Guardian, London, Higher Education Network at this address