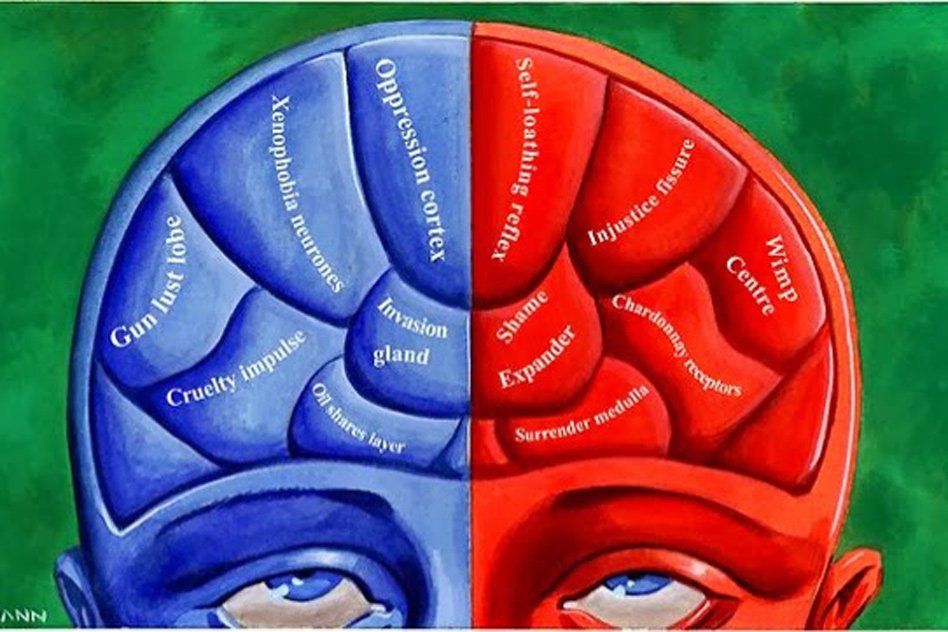

It is imperative to move beyond Left and Right political labels, as Giddens (1994) pointed out thirty years ago. To base the political division of the world’s future on ideological standpoints of left or right is senseless. From the left, right, or in the name of God, human history shows the horror of political atrocities against human beings.

The basis of human progress is not in a return to the past nor the present; it is to anticipate the future, to go forward with the awareness of what could and should have been done and has not been done. The objective is to conceive new ideas, methods, values, and attitudes in an ethical and aesthetic context. One of our purposes in life is to provide a better planet for future generations; it is a moral responsibility and an ethical obligation. Without integrity and compassion, it is impossible to achieve such a goal. And by integrity, we mean ensuring that the things we say and do are aligned. Unfortunately, the current practice of politics does not follow this basic ethical behavior.

Ideological extremists have nearly always taken over Utopias. In the past century and present, they brought in the leftist utopia —communism— or the utopia of the extreme right —Fascism or Nazism— as the only proprietors of the desired goals for human destiny. On the one hand, a betrayal of the collectivist ideal, and on the other, the egocentrism and racism of the minority in control.

Nazism— as the only proprietors of the desired goals for human destiny. On the one hand, a betrayal of the collectivist ideal, and on the other, the egocentrism and racism of the minority in control.

The utopian idea of democracy in terms of the French Revolution was downgraded, and nowadays, liberty, equality, and fraternity are paradigms relegated to the economic sphere. But would it not be possible to build a utopia within the framework of democracy? Isn’t democracy, after all, a utopia? We should begin by analyzing the components of democracy concerning human development.

Freedom produces the paths for development, generating freedom in an inevitable interaction. But the development we refer have a human face; it is global, holistic, and integral. In economic terms, freedom and development do not necessarily interact in the same way; in other words, economic development does not imply freedom. Some dictatorships have had notable economic growth; Spain in the sixties and Chile during Pinochet suffered violations of many of their citizen’s freedom, but their economies flourished. On the contrary, some democratic countries have seen their economy decline. Or, from the extreme left, as in the case of Venezuela or Nicaragua in Latin America, totalitarian governments disguise themselves as a democracy with complete economic failure. The economy is not necessarily a consequence of left-right totalitarian governments. Also, from the left, right, or in the name of God, human history shows the horror of political atrocities against human beings.

So, economic policy must not be confused with freedom, nor democracy with economic development. We need to deal with development in a more comprehensive term. Human development goes hand in hand with genuine democracy and a utopian dimension. No development can be centered on humanity unless society assumes the options of freedom, equality, mutual respect, and fraternity. And this implies eradicating the democratic political practice of five crucial aspects: corruption of any kind, the concentration of power, nationalism and ethnocentrism, lack of education, and the separation of the people from decision-making by the democratic government.

So, economic policy must not be confused with freedom, nor democracy with economic development. We need to deal with development in a more comprehensive term. Human development goes hand in hand with genuine democracy and a utopian dimension. No development can be centered on humanity unless society assumes the options of freedom, equality, mutual respect, and fraternity. And this implies eradicating the democratic political practice of five crucial aspects: corruption of any kind, the concentration of power, nationalism and ethnocentrism, lack of education, and the separation of the people from decision-making by the democratic government.

In an even broader sense, the suppression of frontiers, diffusion of power among the whole people, interethnic development, and respect for minorities are essential to international and intranational progress. Democracies ruled by the Left or Right ideologies in which authoritarian practices are concealed, or any discrimination permitted are guilty of the evil use of power. The learning process often implies a relinquishing of old habits and undesirable behaviors. Politicians must abandon double-talk and half-truths that distort the truth. This habit, ingrained in political practice, primarily when used to win popular support, is dishonest and undermines the democratic system, which should be soundly based on honest and transparent behavior and values.

So, to base the political division of the world’s future on ideological standpoints of left or right is senseless. From the right, from the left, from conservatism or radicalism, and even from the ambiguity of the center, bad policies can be practiced, in which the extremes of the systems meet and melt down. The ideological position that focuses on the complexity of human development cannot possibly be simplified into such vague and empty expressions as these extremes we have mentioned. This political-ideological division of left and right is an anachronism that misses proper human development.

Present political ideologies have a cyclopean view. They cannot see the world in 360 degrees as a gestalt or an independent, fully rounded picture. I agree with Thomas L. Friedman (2016), who, in his book, Thank You for Being Late, states that «the only way you will understand the changing nature of geopolitics today is if you meld what is happening in computing with what is happening in telecommunications with what is happening in the environment with what is happening in globalization with what is happening in demographics. There is no other way today to develop a fully rounded picture.» That’s why neither the left nor the right can solve today’s problems. They were created during the French Revolution of 1789 by the National Assembly members divided into supporters of the king to the president’s right and supporters of the revolution to his left. The division evolved around the rights of individuals and the power of the government for the pre-industrial era, not for today’s fast and technological society, where tomorrow is always late. A new ideological framework with an ethical sense is needed to study the future and its nonstop adaptation and transformation.

Political ideologies and compromises for action must be stated in terms of those who favor human rights and those who violate them; of those who work for the common good and those who extend their freedom at the expense of the freedom of others; of those who distribute equality and those who accumulate privileges; of those who defend diversity and those who try to impose a uniform culture; of those who respect other opinions and those who practice intolerance; of those who accept the will of the people and try to administer the power they have been granted and those who misuse it or turn it to their own benefit; of those who care for the planet’s health and those who don’t; of those looking for the future or of those living in the nostalgic of the past; of those who have an ethical sense of life and those who feel no obligation to humankind.

References

Escotet, M.A. (2022). El desarrollo democrático y la virtual mentira. Diario ABC (Madrid), October 18.

Escotet, M.A. (2020). Pandemics, leadership, and social ethics. Prospects, (UNESCO) 49, 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09472-3.

Escotet, M.A. (1991). Democratic Development and Fraternity as the Ethical Bases for World Politics. International Conference: Helsinki 2000 – The Human Dimension of World Politics. Moscow, Russia, September 3-10.

Escotet, M.A. (1989). Spain and Latin America: The Double Challenge. Geopolitique (Washington D.C. and Paris), 25, Spring, 39-41.

Friedman, Thomas L. (2016). Thank You for Being Late: An Optimist’s Guide to Thriving in the Age of Accelerations. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Giddens, Anthony. (1994). Beyond Left and Right: The Future of Radical Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

UNDP. (1990-2022). Human Development Reports and Human Development Index (HDI). Retrieve at https://hdr.undp.org April 2023.

©2023 Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing.