- January 19, 2023

- Development, Higher Education, HigherEd Management, Institutional Change, Strategic Planning

The development of universities and the intermittent reforms that they undergo are a reflection of the whims of their leaders, although these may sometimes result in appropriate decisions being taken. Reforms and counter-reforms are almost always the results of the appointment of a new president or rector, provost or dean, and not of a consistent line of reasoning or of the exercise of common sense.

Funds may not only be acquired through obtaining material goods or implementing external financing mechanisms. There are also internal sources of funding that stem from the efficiency, effectiveness and appropriateness of the institution itself. Endeavors such as new ways of focusing on teaching and learning, improving quality and relevance, reinforcing systems for communication and interaction with the community that universities provide a service to, enhancing institutional planning and assessment processes and programs, and indeed, renewing an institution’s management processes and promoting the lifelong learning of its academic and administrative personnel would all be appropriate courses of action (Escotet 2023).

Universities require university academic managers to observe the principles of participation, tolerance, effectiveness and efficiency referred to above. These attitudes are not generated spontaneously, just as a surgeon’s skills are not acquired without effort. There are two models in the training of university managers: one that is designed to retrain academics and another that is designed to train university managers from scratch.

The first has the advantage of having first-hand knowledge and experience of university life but at the cost of having to renounce their academic careers; and the second has the drawback of a lack of experience in the difficult task of being the primus inter pares. There is no reason why one model should be favored over the other, as they are in fact complementary. Furthermore, it will be necessary to return to university management strategies from the past and to certain contemporary models, in order to perhaps restructure the government bodies by creating two differentiated management roles, that is, political and administrative management in the form of the chancellor or a similar post and that of the president, rector or provost as the representative of academic management. This distinction, which, it must be stressed, is not a division, of authority based on the collegiate model, would allow two spheres that are not necessarily concentrated in one person or body to be combined.

university life but at the cost of having to renounce their academic careers; and the second has the drawback of a lack of experience in the difficult task of being the primus inter pares. There is no reason why one model should be favored over the other, as they are in fact complementary. Furthermore, it will be necessary to return to university management strategies from the past and to certain contemporary models, in order to perhaps restructure the government bodies by creating two differentiated management roles, that is, political and administrative management in the form of the chancellor or a similar post and that of the president, rector or provost as the representative of academic management. This distinction, which, it must be stressed, is not a division, of authority based on the collegiate model, would allow two spheres that are not necessarily concentrated in one person or body to be combined.

All of the above should be combined with collective structures that represent the society they serve, whether by means of boards of governors, boards of trustees, boards of managers and trade union representatives. It would be useful to test, on the basis of previous experiences, new forms of governance that combine effectiveness  and excellence and to implement education programs that would make university management a truly professional exercise applied to systems for generating and transferring knowledge. New information and communication technologies should also be applied in this regard.

and excellence and to implement education programs that would make university management a truly professional exercise applied to systems for generating and transferring knowledge. New information and communication technologies should also be applied in this regard.

In general, current trends in university management largely continue to be an authoritarian exercise of power that is incompatible with the essence of university practices that demand greater levels of participation. The development of universities and the intermittent reforms that they undergo are a reflection of the whims of their leaders, although these may sometimes result in appropriate decisions being taken. Reforms and counter-reforms are almost always the results of the appointment of a new president or rector, provost or dean, and not of a consistent line of reasoning or of the exercise of common sense.

In short, we need to begin by considering the problem of financing not as a one-dimensional but a multidimensional issue, whose dimensions are, moreover, all interconnected. Accountability in itself is not a sound enough basis for assessing the efficiency and effectiveness of a university, particularly with regard to the quality of creative and teaching/learning processes and the willingness to continue learning throughout one’s life. Nevertheless, at least some government and university policies must be modified, to which McGuinness (2002) and Escotet (2009) refer, in addition to other variables such as those shown in Table I below. But Reform and innovation do not arise, therefore, from a given situation nor do they occur intermittently: it is a continuous, endless process.

| TABLE I Changes in the role of the state and universities in higher education | |

| CHANGES IN: | TOWARDS: |

| Rational planning for static institutional models | Strategic planning for dynamic market models |

| Focus on suppliers, particularly public institutions | Focus on users, individuals who learn (students), companies and governments |

| Areas of service defined by geographic limits and monopolistic markets | Areas of service defined by the requirements of users that are met by multiple suppliers |

| The trend towards centralized control and regulation, in which there are clearly defined institutional aims, financial accountability and retrospective disclosure | Increasingly decentralized management that implements policies to stimulate desirable responses (for example incentives, financing of performance, information for the consumer) |

| Policies and regulations to limit unnecessary competition and overlapping | Policies incorporate the market in the public name and direct competitive forces toward public aims |

| Quality is defined above all in terms of resources (such as professors’ credentials and libraries), according to what is established within higher education | Quality is defined in terms of outcomes and performance according to what is defined by the various users (individuals who learn, entrepreneurs, the government) |

| Policies and services carried out above all through public institutions | Increasing use of non-governmental organizations and public and private suppliers whose aim is to meet user requirements (for example syllabuses and learning modules that are subject to continuous change, student services, skills determination, quality guarantee) |

| Regular financial and quantitative accountability methods and methodologies | Internal and external continuous assessment systems that are part of academic management and administrative processes |

| Teaching systems that are based mainly on oral transmission and the distance between professors and students | Teaching systems that are based on new technologies and tailor-made methods for professors and students to share knowledge |

| Culture is based on the individual who teaches and the individuals who administrates | Culture is based on the individual who learns (student, professor/researcher, administrator) |

| Universities are isolated from society and from the industrial fabric and companies are isolated from universities | Higher education is involved in social capitalization processes and is linked to society’s creative and industrial systems |

| Public and private industrial system that is not involved in funding society’s system for training qualified professionals | Public and private companies that contribute financially to universities according to the number and type of graduates they employ (training repayment) |

| Universities that perpetuate traditions, corporatism and the slow evolution of processes, technologies, and value systems | Universities that innovate, are continuously changing and are rooted in a profound sense of ethics and aesthetics |

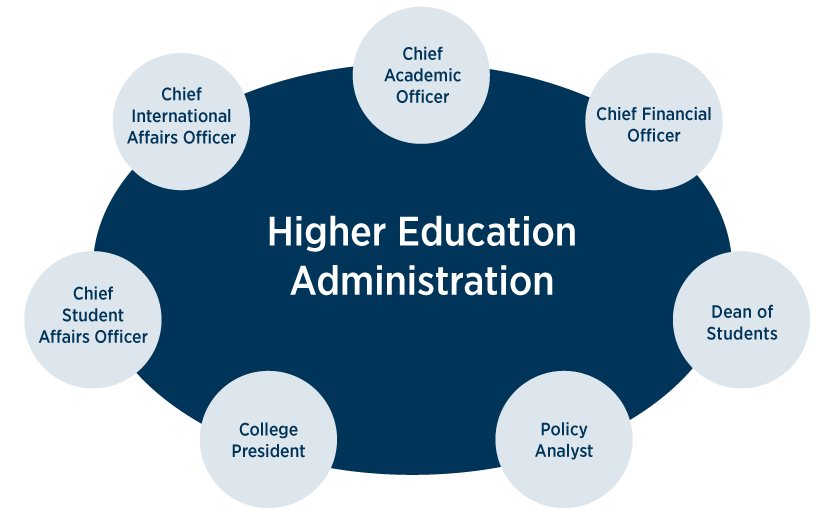

The figure immediately below represents the typical functions of university or higher education administration in terms of major areas of management. On the other hand, it is a need in changing the role of the state and institutions of higher education. One of the most important changes relates to combining the need for the best quality higher education that is affordable for low and middle-income families, nationally and internationally.

At the national level, many countries have different public funding systems for vocational training based on resources obtained by taxation or para-fiscal contributions for specific purposes, especially in relation to the ‘training skills’ of corporation employees. There are various formulas for the funding by companies of their employees’ education, such as taking a percentage of their salaries or a proportion based on their social security contributions, as occurs at INCE in Venezuela, SENA in Colombia, SENAI in Brazil and FORCEM and OBETUS in Spain.

There are no procedures in place for companies to reimburse universities for using their resources and human capital. It would be fair for training costs to be covered by industry, whether public or private, by means of the proportional reimbursement of the costs of training each of the university graduates who are employed at a company, to the institution or institutions that educated them.

There are no procedures in place for companies to reimburse universities for using their resources and human capital. It would be fair for training costs to be covered by industry, whether public or private, by means of the proportional reimbursement of the costs of training each of the university graduates who are employed at a company, to the institution or institutions that educated them.

This model would require the establishment of alliances or associations between the state, universities, other accredited institutions of higher education and business organizations, as well as public enterprises and government bodies in their role as employers. Public and private companies would have to contribute, over a given number of years, a training repayment percentage or tax to be determined from the total sum of the wages, salaries and remunerations of any kind, paid to the university graduates who are employed at those companies. At the same time, the state would have to establish a system of tax incentives to allow companies to indirectly recover their investment in human capital. Finally, universities should be subject to academic auditing to ensure that they use training repayment funds appropriately, beyond the accountability processes that already govern the university system.

In the international sphere, the problem is even more complex. The brain drain problem may  be seen as a subsidy paid by poor nations to wealthy nations for the purposes of vocational and university training. The country that takes in the professional benefits from the investment in human capital made by the issuing country. This includes not only the cost of higher or technical education but also the cost of schooling at the primary and secondary levels. The situation is even more calamitous if we consider the fact that, for a developing nation, the financial effort required is ten times that which a wealthy country would have to make. That is, the wealthier a country the more money it can put towards education and the cheaper the cost of this money. The situation is exactly the opposite in poor countries.

be seen as a subsidy paid by poor nations to wealthy nations for the purposes of vocational and university training. The country that takes in the professional benefits from the investment in human capital made by the issuing country. This includes not only the cost of higher or technical education but also the cost of schooling at the primary and secondary levels. The situation is even more calamitous if we consider the fact that, for a developing nation, the financial effort required is ten times that which a wealthy country would have to make. That is, the wealthier a country the more money it can put towards education and the cheaper the cost of this money. The situation is exactly the opposite in poor countries.

It would be necessary to establish an international justice and solidarity system in which the country that receives the qualified emigrants reimburses the country that invested in those human resources. This is one of the most pressing issues that must be addressed internationally and one of the gravest problems faced by poor or developing nations in terms of financing their education systems. Not only do they lose their human capital but there are countries that benefit from this investment without incurring any costs whatsoever.

It is imperative that we address this problem, which is worsened by globalization and the creation of superregional structures that tend to exacerbate inequalities and a lack of symmetry in the processes of generating and transferring knowledge, as well as impoverishing the countries that are on the receiving end of technology.

References

Altbach, Philip G. (1997). Comparative Higher Education: Knowledge, The University, and Development. Boston: Boston College, Center for International Higher Education.

Arnove, Robert F. and Escotet, Miguel A. (2013). Reflexiones y tendencias de la educación comparada e internacional. En UNED (Ed.) Conversaciones con un maestro (Liber Amicorum). Madrid: Ediciones Académicas, 25-34.

Escotet, Miguel A. (2023). La universidad del futuro para una educación en red y a lo largo de la vida. En Santos Rego, M.A., Lorenzo Moledo, Mar y García Álvarez, Jesús (Eds.). La educación en red. Una Perspectiva multidimensional. Editorial Octaedro, 161-192.

Escotet, Miguel A. (2013) La Universidad y las políticas sobre nuevos aprendizajes en un mundo global. En Santos Rego, M.A. (Ed.) Cosmopolitismo y educación: Aprender y trabajar en un mundo sin fronteras. Valencia: Editorial Brief, 149-162.

Escotet, Miguel A. (2009) University Governance, Accountability and Financing. In GUNI (Ed.) Higher Education at a Time of Transformation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 126-132.

Griffin, Gabriele (2022). The ‘Work-Work Balance’ in higher education: between over-work, falling short and the pleasures of multiplicity. Studies in Higher Education, Vol 47, 11, 2190-2203.

McGuinness, Aims C. (2002) Reflections on Postsecondary Governance Changes. Boulder: Education Commission of the States.

OECD (2002) Managing Public Expenditure: A Reference Book for Transitional Countries. Paris: OECD.

Sanyal, Bikas and Martin, Michaela (2005) Financial management in higher education: Issues and approaches. Workshop on Higher Education by MTAC (Uganda) and International Institute for Educational Planning (France).

——————————

©2023 Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing.