- December 21, 2016

- Education, Educational Philosophy, Educational Theory, Ethics, HigherEd Theory & Praxis, University Policy

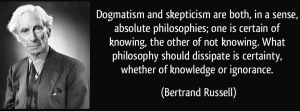

Dogmatism and rigidity in the university are sources of intolerance, authoritarianism and conflict. Moreover, flexibility is not a synonym of weakness; on the contrary, it is a symbol of spiritual fortitude that grows when it rectifies mistakes and discovers its own ignorance.

Higher education reform and innovation is a continuous, endless process. To remain in the same place one must keep moving; otherwise, one gets left behind. This dynamic requires social organisations to be more than passive onlookers.

Universities should be at the cutting edge. They should develop their capacity for anticipation so that they are able to respond to the trust placed in them by society, acting as a compass that guides society’s progress and wellbeing.

Universities should have a long-term vision, nurture innovation and foster creativity. Universities of this type do not need to pause to institute reform, nor do they need a new academic leader, because reform and innovation come naturally to them.

All university crises, acts of political reform and modifications made by the government or by university authorities have been superficial changes. These acts have led to complex laws and regulations that have reinforced the rigidity of universities’ structures and processes, even when they are well-intentioned.

There has been a general trend to equate university reform with changes in legislation. A greater emphasis has been placed on the form rather than the content. An excess of regulation is one of the main reasons why contemporary universities do not change. It is the responsibility of the university community to create a culture of change, a sense of constructive self-criticism and the capacity to rectify in time.

There has been a general trend to equate university reform with changes in legislation. A greater emphasis has been placed on the form rather than the content. An excess of regulation is one of the main reasons why contemporary universities do not change. It is the responsibility of the university community to create a culture of change, a sense of constructive self-criticism and the capacity to rectify in time.

Continuous reform and innovation require open and flexible regulatory bodies and a desire for change that should be imprinted on the consciences of the university community. Without these conditions, any attempt to push for change will be a lost opportunity. Or, in the best case, a move forward that will simply widen the gap between universities and change itself. If, on the contrary, the aforementioned co nditions are met, or an attempt is at least made to bring universities closer to them, reforms will cease to exist, because universities would be undergoing continuous change.

nditions are met, or an attempt is at least made to bring universities closer to them, reforms will cease to exist, because universities would be undergoing continuous change.

Herein lies the key to all universities’ aims: “to educate human beings for continuous change and even for the crises that will be the result of transition” (MA Escotet 1997, University and Becoming, Buenos Aires, Lugar Publishing). Universities should not just be rooted in change and innovation, they also need a sense of ethics and citizenship.

Dogmatism is not a part of university culture. Rigid thinking clashes with the principles inherent to the pursuit of truth and with the endless breadth of knowledge. Just as diversity instigates creativity, flexibility fosters change. In the absence of flexibility, everything remains the same.

Dogmatism and rigidity are sources of intolerance, authoritarianism and conflict. Moreover, flexibility is not a synonym of weakness; on the contrary, it is a symbol of spiritual fortitude that grows when it rectifies mistakes and discovers its own ignorance.

The expansion of knowledge and the degree of certainty are inversely proportional. In the measure in which one is educated, the more one knows and discovers, the more one becomes certain of one’s lack of knowledge of the universe, which drives one to keep learning. For this reason, intellectual vanity is not an attribute of those who know their limits, but rather of those who pretend to know what they do not know.

the more one becomes certain of one’s lack of knowledge of the universe, which drives one to keep learning. For this reason, intellectual vanity is not an attribute of those who know their limits, but rather of those who pretend to know what they do not know.

Knowledge does not admit vanity or egotism. Participation is the opposite of authoritarianism and to know in order to share and to give honours humankind. Governing universities in the absence of the full participation of the university community and society will inevitably push them towards forms of authoritarianism that are contrary to their spirit and their ethical practice.

——————————

Miguel Angel Escotet is an emeritus professor and former dean of the College of Education at the University of Texas – UTRGV. He is presently, President of //Afundacion and Corporate Social Responsibility DG of //ABANCA.

This essay was originally published by The Guardian, Higher Education Network at this address

©2012, 2016 Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing.